Trust or distrust in medical images is contextualized. Depending on their specialty and level of qualification, doctors develop different relationships with medical imaging over the course of their practice. It's true that, thanks to extensive training, all doctors develop a “skilled vision” (Grasseni 2007) and acquire scientific skills that enable them to read medical images and “see” things on an MRI, PET-SCAN or X-ray that uninitiated patients would be unable to detect. But on the one hand, the ability to read medical images varies from one specialty to another (radiologist, neurologist, oncologist, etc.). Secondly, medical imaging cannot stand alone. It is always part of a network that links it to other artifacts of hospital knowledge. Upstream of image acquisition, the patient's clinical history influences the physician's prescription, who tells the technician which part of the body to explore and what to look for. Downstream, the prescribing physician is informed by previous images for comparison, and by a report from the radiologist at the acquisition center. All these different visual and written artifacts are elements that enable us to recontextualize the medical image and “make it speak”. This is all the more true for autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, whose diagnosis cannot be based on medical imaging alone. The specificity of this disease, with its diverse symptoms and sometimes invisible lesions, can make it difficult to diagnose by simple MRI acquisition. In the words of a neurologist with whom sociologist Kelly Joyce conducted her fieldwork, “The MRI scan is probably negative up to 25% of the time in [MS] cases, so I would usually trust my exam much more than the MRI scan” (Joyce 2005: 452).

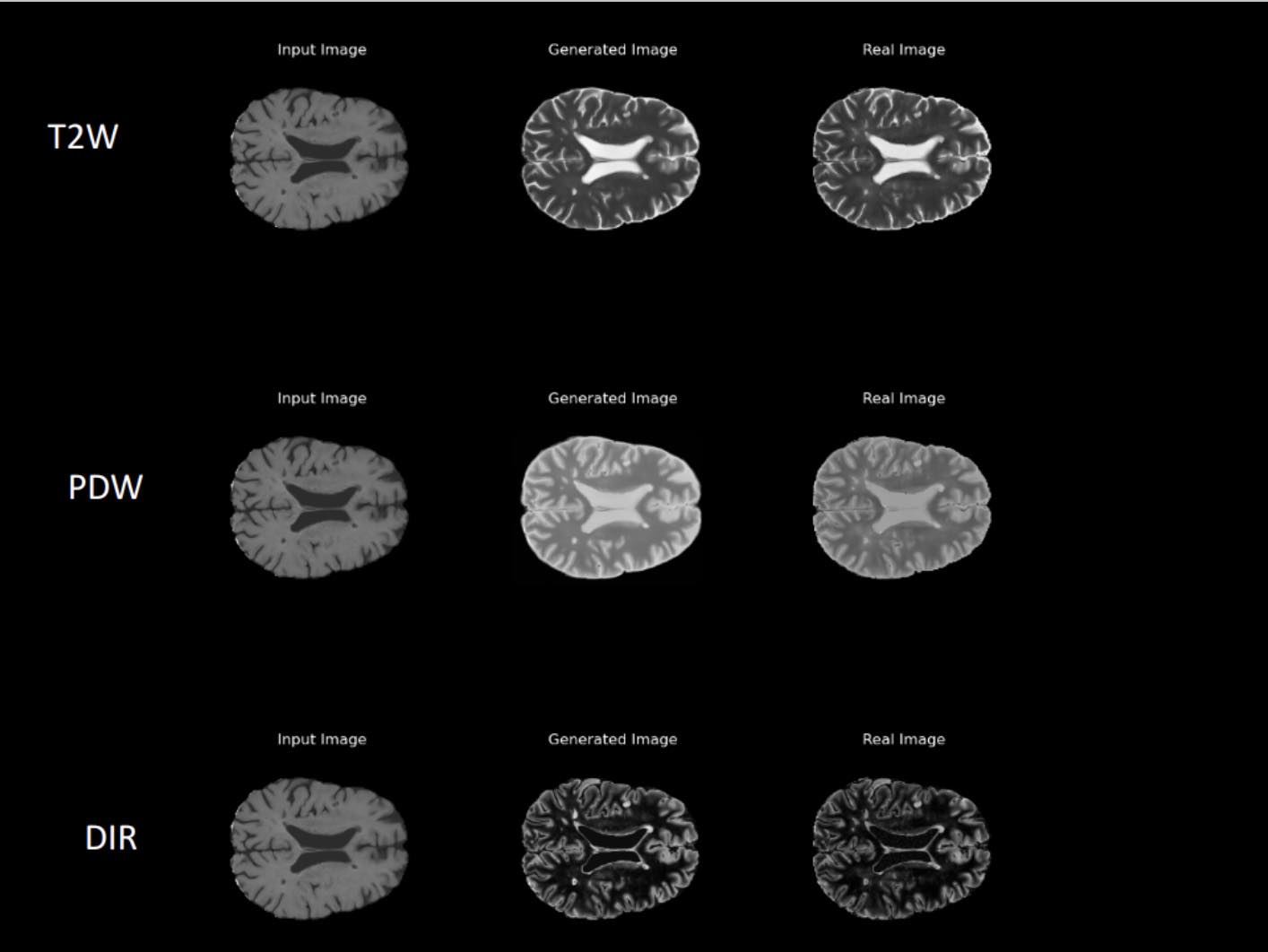

20 years have passed since that interview. Protocols have since greatly evolved, considerably increasing the precision of MRI scans and their relevance to diagnosis. To put it simply, radiologists and neurologists can now better “see” the traces of the disease on their patient's brain. However, ambiguity and uncertainty remain. Some lesions can be mistaken for acquisition artifacts, traces that are not signs of the disease, but defects in the MRI manufacturing process. The reverse is also true: artifacts can be interpreted as lesions. To ensure a correct diagnosis for the most difficult cases, i.e. those that leave the most room for uncertainty, one Thursday a month, the neurologists specializing in multiple sclerosis at one of Barcelona's largest and most prestigious hospitals meet to discuss their patients' MRI. In some cases, the collegiality of the group makes it possible to remove doubt and rule out, or confirm, the disease. Some cases, however, remain unresolved. Beyond an objectivist conception of medical knowledge and its tools, the doctor must know how to manage the uncertainty of disease and the intrinsic ambiguity of any medical image, which more than any other artifact carries the myth of transparency (Joyce 2008).

Bibliography

GRASSENI Cristina (ed.)

(2007) Skilled Visions: Between Apprenticeship and Standards. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

JOYCE Kelly A.

(2005) “Appealing Images: Magnetic Resonance Imaging and the Production of Authoritative Knowledge”, Social Studies of Science, vol.35, n°3, p.437–462

(2008) Magnetic Appeal: MRI and the Myth of Transparency. 1st ed., Cornell University Press

Back to the list