Between 12 and 14 October 20223, I attended the symposium Art and Science in Visual Research, held at the University of Antwerp in homage to Professor Luc Pauwels.

I would like to briefly summarize some of the ideas that came into my mind during the congress. I presented some of them publicly in order to trigger the debate.

Ethics, visual, and experimentation: we usually present ethics and ethical concerns as a kind of burden that goes against freedom, experimentation and creativity. Ethics is indeed often described as a set of rules, prescriptions and obligations that we have to fulfil during the research. Why do we have this idea of ethics? I think that part of the answer lies in our increasingly legalistic understanding of ethics and in a solipsistic and romantic conception of art and creativity.

Indeed, as researchers, we are increasingly obliged nowadays to comply with legal procedures when doing research. This is particularly clear when doing visual research. We are pushed to use informed consents and to make people sign documents, use ID identifications, and be part of a general bureaucratic language based on the abstract ideas of “rights” and “obligations”. There are reasons to justify these procedures: for years, researches have not been honest enough when presenting the objectives and procedures of their investigations. They have not shared the outcomes of their research with those who have made them possible.

Yet, I think that an ethical attitude is much more than that. It is a way of taking into account other people’s concerns and inner understandings of the nature of the relationships that we build altogether. In this regard, ethics cannot be “applied”: it is rather something that we generate, and that can give us new insights about other ways of conceiving and inhabiting the world. My point is that we can take these insights as points of departure for exploring new ways of doing and representing research, that is, of experimenting.

As I said, any act of creativity is an act of de-centring. And ethics is about de-centring.

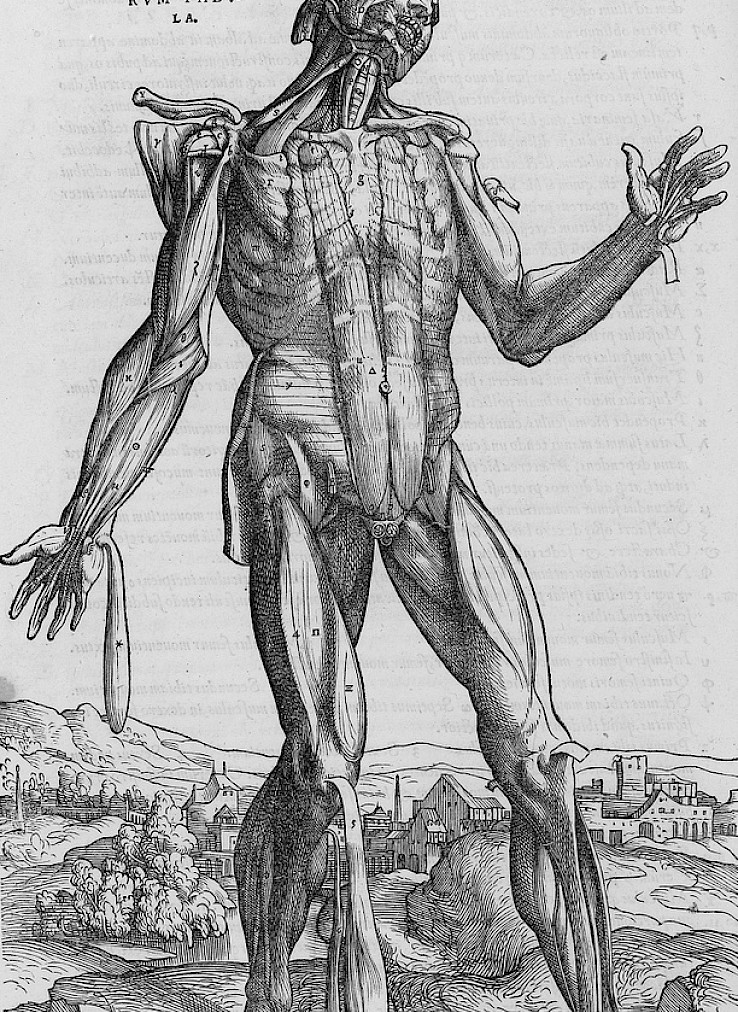

Data as image and image as data: we constantly turn data into images and images into data. Images are increasingly regarded as data in the sense that what really matters to them is not what they actually show, but the amount of information (call it “metadata”) which is associated with them and which can generate a value -be it economic, military or whatever. This is particularly clear in the case of photographic images in fields like photojournalism. There, metadata is used to authenticate the origin of the image. But there are other examples: surveillance cameras generate units of information and so are digital images uploaded on the internet, which are used as patterns for machine-learning and computer vision. Perhaps even artworks are increasingly evaluated in terms of metadata (the information attached to the image, and not the image itself).

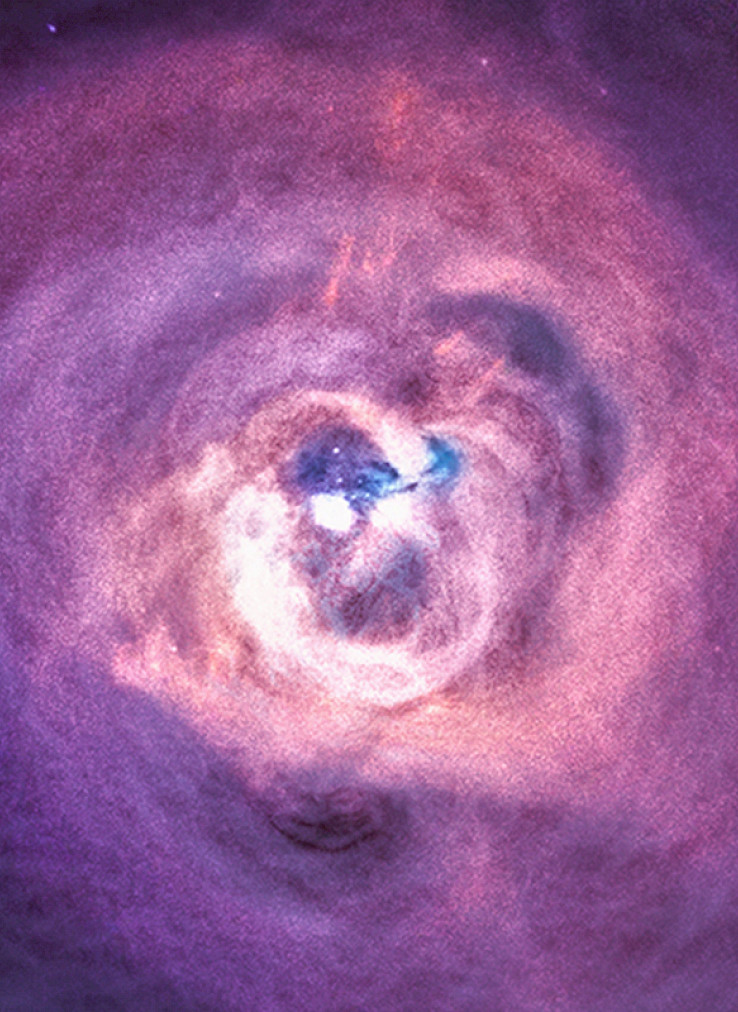

On the other hand, data is constantly turned into images, understood very broadly as visual devices or visual signs. Luc Pawuel calls it “visualization”. So, we visualize data according to a set of aesthetic patters and conventions stemming from a long history of geometrics, diagrams and graphics. Sometimes these graphics are beautiful, and we trust them not only because we consider them to look like science, but also because they create on us a sensation of awesome and beauty. They are a sort of revelation.

Perhaps all images have always had some kind of “metadata”. Perhaps the action of turning data into images is not that new either. In a way, images have always referred to what cannot be seen directly. But there is an increasing overlapping of both concepts which prompts us to think data and images as an inseparable pair.

Images as forms of anticipation: the realistic paradigm of photography stated that photography shows us what has happened. They are a trace of the past in the present. This idea has forged our way of understanding images of visual evidences. However, today we find a lot of images which are not meant to depict what has occurred, but rather to visualize what may occur in the future. In this regard, these images, some of which may look like a “real photograph”, act in a performative way: in a more or less explicit manner, by showing how the future might look like, they shape our imagination and thus forge the way the future is likely to be. Anticipation is a form of control. Surveillance images, for instance, are also used to predict future behaviours and turn them into visual models that are used to anticipate eventual undesirable events. In conclusion, the future is visualized in images -and images are used as a resource to present visually possible scenarios that are not just set out as a mere possibility, but rather as a kind of unavoidable fate.

IA and human agency: it is one of the debates in IA-based art: is this a way of going beyond human agency? That is, of de-centering the human? Because, in a way, all IA is very human (it is a human artifact). And it is “going beyond the human” through a machine working through algorithms a desirable thing?

The participation in this symposium was part of my ERC project VISUAL TRUST. I really enjoyed the days I spent there and I want to thank the local committee who made this congress possible. These were three days of inspiring discussions between students and scholars of different ages and nationalities.

Back to the list