The vision we have of reality and the ways of representing it, such as through images, have always given rise to great debates. And I am not only referring to the field of photography or the media, but also in everyday spheres, where the image is so present. One of the reasons is that, through the images that are published and communicated by different media, we shape our view of the world. These images also invite us, in a more or less forced way, to form an opinion on the subjects they represent. Sontag, one of the most important sociologists and image theorists, points out that photographs do not shape public opinion, but they do help us to take a position.

From this idea, we can ask ourselves how our way of looking relates to our surroundings. It also invites us to think about how our experience of the world becomes a way of looking, and how photography becomes a way of recognising the landscape and a way of noticing and learning about it.

On the other side of this process we can find the one who creates the image. The photograph is always a trace of the person who generates the image. A photograph can be produced as an information document, for an art market, as self-exploration, or as ideological positioning, among others, but it always implies the creative intimacy of the author. Related to this, we could say that vulnerability, understood as a person's most emotional and exposed space, is often the driving force of creation and speaks to us of thoughts, desires and ways of life, not only individual, but also communal.

By recovering the idea of the imprint that images leave on us, we can understand their transformative power in society and to establish spaces for reflection. In this context, the new visual proposals take an important position as a concrete gaze in the definition of the world - as Tarkovski says, an image is not the representation of reality, but "a concretion" of it. Therefore, what we can find in some of the new creations a reflexive proposal on how we approach our surroundings and the image as a mediator between the world and ourselves.

The author, in this case, despite the fact that in a first experience he photographed these events in person, for the present project he proposes a construction with images that, to a certain extent, have already been captured before. However, the figure of the photographer remains essential for the coherence and ethics with which the discourse is constructed.

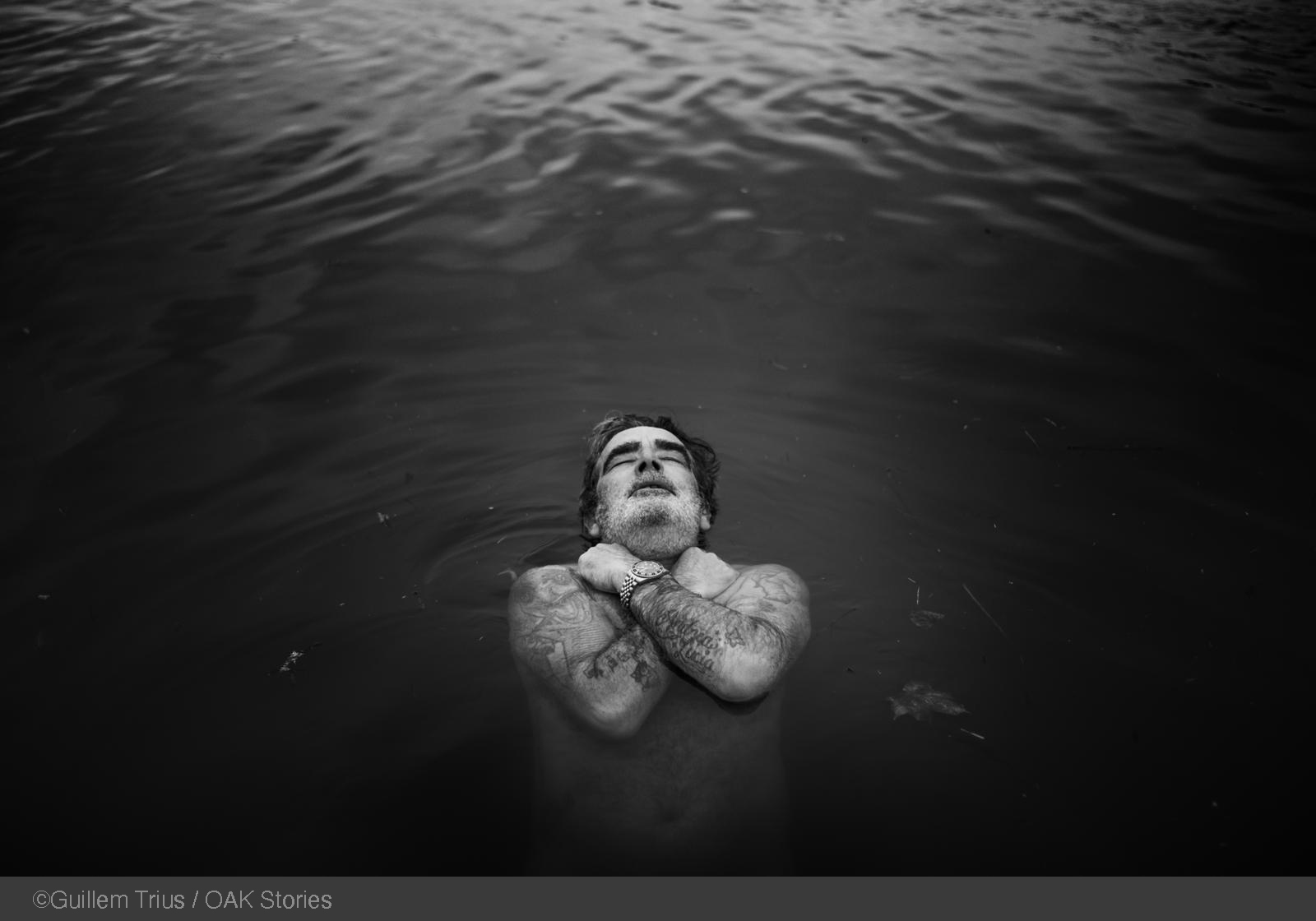

On the other hand, we can also look at the "Norden" project of the photography agency OAK Stories, with whom I was able to follow with the photographer Guillem Trius during his time in Norway. In the cover image of this text, belonging to this project, we see a photograph that goes beyond the purely documentary and suggests relating to our surroundings from a more intimate, reflective and involved space. In this sense, Trius amplifies the narrative capacity of the image, freeing it from the literal traditions for explaining the world and taking it to a place of greater significance.

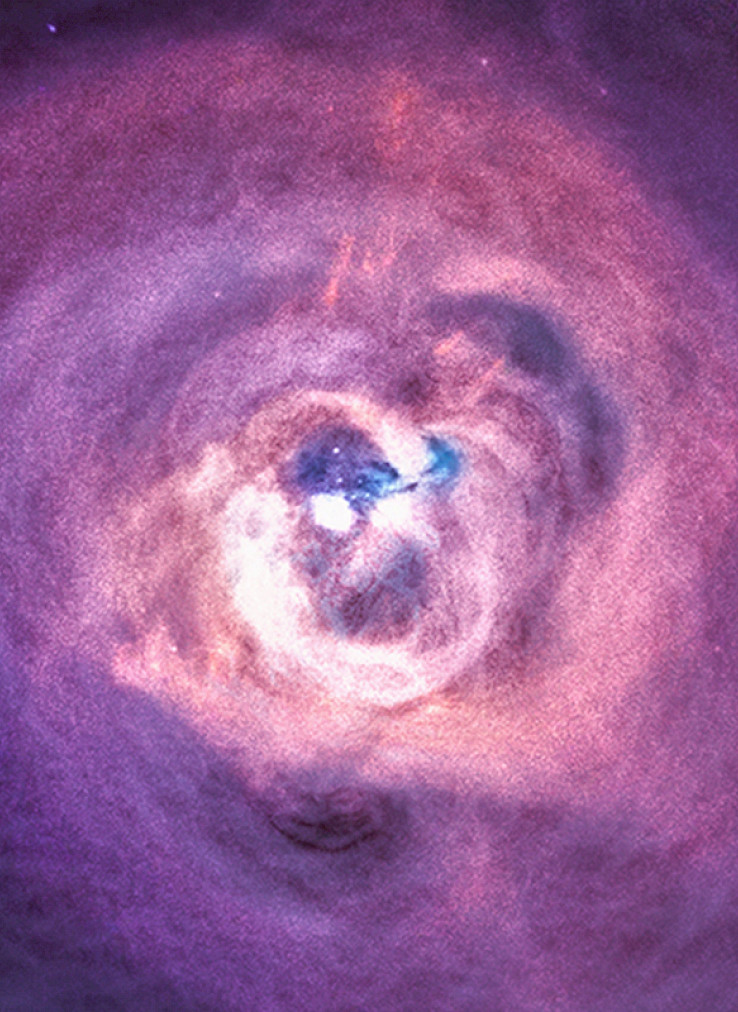

Nowadays, we also find ourselves in a context where technology offers new tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) and begins to raise doubts about any image we can see. Some projects such as those of Ana Belén Jarrín, Inzajeano Latif and Roope Rainisto, based on photographic manipulation and artificial intelligence, also propose possible realities - past, present or future - that present us with alternative experiences of our stay in the world. What do these projects speak to us about? Fears, desires? What do we seek through these images and what expectations do we want to satisfy in their visualisation? But, couldn't we transfer these same questions to creations prior to AI? How do these new tools relate to previous manipulations such as those of historical photographic archives or the documentary press? These and many other questions fuel current debates about the creation of images with artificial intelligence, and continue to raise threat or disquiet among some viewers.

For all of the above, we can conceive of the photographer as a mediator of our experience of reality and as someone who brings us a concrete view of the world and new reflections. This mediation has been going on since the beginning of the humanity - cave paintings were also a way of mediating with the outside world. Even so, the current casuistry introduces a new paradigm shift, proposing a new possible status for the photographer, becoming a "creator of visual content" and thus broadening the ways of constructing the image, while maintaining - since it is nothing new - the implications of message, ideology and positioning inherent in the image created.

It is also interesting to realise how the image is a neutral element, but not the intention with which the photograph is taken or the visual content is created. In an interview with the informant of the Visual Trust project, Gaël Morel, curator at The Image Centre in Canada, she stated: "Photographs don't say anything, we make them say". Following this thread, the image theorist WJT Mitchell, reminds us of the "paradoxical structure" of the image, previously noted by Roland Barthes. He argues that this contradiction coincides with an ethical antilogicality at the moment when the image attempts to present itself as neutral by its creator or communicator. According to Mitchell, Barthes presents the coexistence of two messages in the photograph, one "without code" - the denotative or denotation - and the coded message - the connotative or connotation -. In this sense, the author notes how a connotation or coded message in a photograph is a pure denotation. Or said in the other direction, every image that has a specific treatment in terms of message, rhetoric or writing is also a photographic analogue form, with no more charge than a handful of shapes, colours and dispositions on a support. And that is why Mitchell argues that "the value of photography lies precisely in its freedom from values (...) its main connotation or coded implication is that it is pure denotation, without code".

The concepts of denotation and connotation are really intriguing to me when we talk about documentary photography or photography that claims to have a "credible or trustable" link to the material reality of the world. Connotation, on the one hand, points to the "roots of photography" and implies "the choice of subject matter, angles and lighting" (Mitchell 1995). On the other hand, denotation is anchored in the "most textually readable characteristics" of a photograph, interpreted as a trace, spoor or relic of an event.

For all of the above reasons, it will be not only interesting, but essential to continue discovering and thinking about the forms of representation, their possible uses and how they are integrated into the fabric of our societies. In this sense, to emphasise our understanding of how photographs are encoded and decoded, serving a multiplicity of uses, always changing and rooted in specific socio-cultural and political situations. For this, it will be necessary to get rid once and for all of the supposed neutrality of images, especially those that we call "documentary" and are often embedded in the media. The image must be given the freedom it deserves. Only in this way will we obtain all that it can give us.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1995). Picture theory: Essays on the verbal and visual representation. University of Chicago Press.

Tarkovsk, Andrei (1996). Esculpir en el tiempo. Libros de Cine, Rialp.

Part of this article was first published in the online newspaper El Cugatenc: https://www.elcugatenc.cat/opinio/84280/apunts-sobre-com-mirem

Back to the list